|

| George Washington Cox |

It all started with a book. Roland and I were at the Friends of the Library in Stockton, a frequent haunt of ours, when we found an older, historical book about the gold country titled, Motherlode Memories. Roland purchased it and started going through the pages in the car. He pointed out to several places we are familiar with and a few we hadn't seen before. This past weekend he pulled out the book and said, "Let's go up to San Andreas, and see if we can find these two men's graves so I can put their photos on Find-a-grave."

The two men he was speaking of were Sheriff Ben Thorn and Judge Gottschalk. They were the two men pictured on the pages in the historical book he was looking at. The page also showed a photo of the backside of the courthouse with a small blurb underneath that read "The courtyard in the rear of the restored 1868 San Andreas courthouse and jail was landscaped by the students of San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton. The last hanging from the gallows in this courtyard occurred in 1870." - (pg 102, Motherlode Memories). The page also had photographs of the Black Bart Inn and Ben Thorn's house as well. In the usual way that we do, we jumped in the car and headed up to San Andreas to do some history hunting.

We searched for Pixley Lane and found ourselves going up a windy road up to an old cemetery on top of a hillside.

|

| People's Cemetery, San Andreas, CA |

We wandered the grounds for a good hour or longer, before I stumbled upon Judge Gottschalk's grave, but we never did find Sheriff Thorn. As we were leaving the cemetery, we passed by a reddish marble stone that read George Washington Cox. I noticed the name right away, and Roland even spoke his name out loud as we passed by. It was apparent that we were meant to see or acknowledge that grave for some reason, but at the time we didn't know why.

So up to the Courthouse we drove, to take photos of the buildings on the main street. As I passed by the courthouse steps I noticed that they were open, so I walked right on in. I met up with a docent there and started talking to her about another story I have been planning to write about that took place in Valley Springs, and I wanted permission to use the Historical Society's photograph for my blog. We started talking and I gave her one of my business cards and Roland purchased our tickets to take a tour of the courthouse museum.

The courthouse upstairs is beautiful, and preserved just as it was when Judge Gottschalk sentenced the infamous Black Bart to prison for his stage coach robberies throughout the motherlode. But it wasn't the courtroom that intrigued me, it was the jail that I wanted to see. As I walked down the brick walkway down the side of the old courthouse and made my way around to the back yard of the property, I recognized the scene from the old black and white photo in Roland's book. This was the spot where the last hanging occurred.

"I wish I knew who that person was", I told Roland, as I walked up to the back steps of the jail.

"Look, I am going to jail," I said, as I made a hand gesture as if I was handcuffed in front. I smiled and I walked into the jail.

It was quiet and dark. Suddenly the motion censor lights came on. It startled me, I cannot deny that. Nothing paranormal about it though. I made my way to the back hallway where the cells were. I walked into one of the cells and tried to imagine how it must have felt to have been incarcerated there. The etched names and initials carved into the walls were abundant. Who were these men? What stories did they have to tell? Were any of them among those who met their ending just steps away in the back yard?

As I walked around, filming my experience there, Roland called out to me.

"Hey, come over here," he said. "Remember that grave in the cemetery , George Washington Cox? He was the last guy they hanged here."

I walked into the small room off the main jail entry way, and there it was: a glass case with chain mail on display, a photograph of George, a small invitation to the ghastly affair (his execution) and at the bottom was a photocopy of a photograph of a man and woman (possibly George and his wife?) and a letter in his own hand, made out to one of his daughters, Medie Cox Damon, written just a month before he was hanged.

It seemed too coincidental to the both of us that we both noticed his grave at the cemetery earlier, and then like following invisible footsteps on a map, we happened to end up at the very spot in which George met his final ending. I sat down on the concrete floor and read his letter aloud. Roland had stepped outside to take more photos. No one was there, and I was all alone in the jail. You could hear a pin fall it was so quiet.

The letter read:

"Saturday, July 6th, 1888

My Dear Daughter,

|

| Cox's Letter |

Yours Affectionately,

G.W. Cox"

I sat there at the jailhouse and started to cry. The letter seemed very sad, and the thought of a person's life ending and those were his last written words to a loved one really got to me. I wanted to know more. Why did he hang? What did he do? What happened?

There was a small paper in the glass cabinet that shed further light on the story.

"George Washington Cox goes down in Calaveras County history as the last man hanged in the jail yard. Soon after his hanging, the privilege of conducting hanging went to San Quentin.

Cox shot his son-in-law while having paranoid delusions of him having an affair with his wife. After he had shot and killed him, he put his armor on and gathered his knives and turned himself in to Ben Thorn, the county sheriff."

Well, it wouldn't be the first time a son-in-law was caught sleeping with his mother-in-law, trust me, I know of a few stories personally in the last few generations that this happened in different families.

But, did George's wife and son-in-law actually do that? I needed to know more.

We drove back up to the cemetery for the second time in the same day, and went right back to that grave we had passed by just a few hours earlier. I stopped and his grave and sat down, I took photos and I read out loud the letter he wrote to his daughter. I wondered, did his daughter ever read the letter? Or was she too distraught over the whole situation that she never accepted it, and thus it ended up back at the courthouse among items on display at the museum?

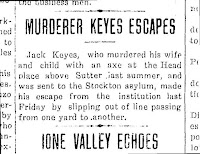

As soon as we left and returned home, I started searching the archived newspapers of the time to see if I could dig up anymore on this perplexing story.

The first thing I wanted to see was if he had a memorial on Find-a-grave, and he did.

So, I kept searching the archived newspapers of the time, to see what light I could shed on this story that literally found me.

The Amador Ledger, dated November 12, 1887 elaborated a bit more:

|

| Cox's items on display at the Jail. |

Cook stood up and then fell to the floor, Cox firing another shot as Cook fell, which struck the table in front of the little boy. Mrs. Cox and Mrs. Cook were in the room when the second shot was fired and before Cox had reloaded his rifle the third time, Mrs. Cook sprang across the room and caught hold of the gun and pushed Cox into the hall. During the struggle Cox kicked his daughter and struck her on the head with the rifle, which knocked her down, but she got up and pushed Cox out of the house and locked the door.

Cox went to a window and pointed his rifle at Mrs. Cook and swore he was prepared for any of them. In all probability Cox would have killed his wife and daughter had not the latter caught the assassin and put him out of the house by main strength. There appears to have been no cause whatever for committing the murder. There had not been an angry word spoken that day, or on any previous occasion by either of the men to one another. the coroner's jury charged Cox with having committed a cold-blooded murder. "

So by that point, it appears the rumor about his wife's infidelity hadn't gotten around in the community just yet. So when and where did this rumor start?

Digging into the archived newspapers little more, I found that a friend of Cox's, a Mr. Dave Reed, came to the authorities to tell them that just after Cox had killed Henry Cook, he came over to his Reed's cabin and asked him to help him gather his belongings from the house. He didn't tell Reed what had just transpired, so when Reed went into the house to get Cox's belongings he didn't know why everyone was crying. He gathered his things and left. Soon after, Mrs. Cox went to Reed's cabin and told him what happened and Reed went back to the house and went into the dining room and saw Mr. Cook dead on the floor. He claims this was the first he knew about it, when Mrs. Cox told him.About fifteen years ago, a historian by the name of Walt Motloch shared more information to journalist Dana Nichols for a piece in the Stockton Record. Motloch uncovered even more regarding the story, which didn't necessarily settle the rumors, but instead created more confusion about the motive of the killing itself.

According to the news article dated in 2007, three different descendants of George Washington Cox have come to three different conclusions about what happened. Joette Farrand, a great-great granddaughter of Cox, believed he was set up, and that there were people who wanted to get him "out of the way," so-to-speak. Now, this goes in line in a way with what Cox speaks in his letter about a "band of dishonest men."

Was he speaking about certain people plotting against him? Feeding him with false ideas? Knowing all too well he was like a ticking time bomb ready to go off at the next rumor that he heard? Or was the "band of dishonest men" simply the jury who convicted him?

The next descendant, Lee Rude, claimed that he had heard Cox had abandoned the family for 12 years, and only returned around the time of the murder. According to the Record's account, the Calaveras Prospect mentioned that Cox was a drifter who went from place to place, job to job and came back to seek revenge on the "injuries done" to him.

But what were these great injuries done to him? And why his son-in-law, unless there actually was a reason for the killing?

Lastly, Jan Cook, another one of Cox's great grandchildren eludes to the idea that he was mentally unstable, not knowing where he was half the time, and being "weak mentally." So was he mentally incapacitated at the time of the murder? If so, why not send him to the Stockton Asylum? Why condemn him to the gallows?

The more information being spread the more confusing it had became.

Do I believe he specifically came to Calaveras to exact revenge on his son-in-law? I am not sure. But where did he get this information that his wife was being unfaithful in the first place? It had to come from somewhere. Was he upset that he spent years of his life, working wherever he could to make a living (possibly sending the money to his family) only to find out his wife was sleeping around?

First and foremost, I am not accusing his wife of something that hasn't been said before. For the record, I don't know if she was faithful to him or not, just as I don't know whether Cox had any true merit to his accusations against her. But something was going on, whether it was reality or all in his mind. And if it was all in his mind, again, why did the jury not seek to send him to the Asylum in Stockton?

By Cox's own admission during his trial, he believed his act was a defense to his family. Why would he say that if he didn't feel a real threat to himself or his family?

The article in the Stockton Record from 2007, claims that Cox later admitted (after his trial) that the rumors he believed about his son-in-law were unfounded.

But where is this documentation? (Not to say it wasn't said, but I would certainly like to see that for myself).

The Sacramento Daily Record Union, dated September 1, 1888, gives a little more insight into Cox's state of mind when he killed Cook when it reads, "The crime for which Cox suffered the death penalty was for the murder of his son-in-law, Henry Cook, near Sheep Ranch, in this county on November 3rd last. The murderer shot the young man while he was eating dinner, without any warning whatsoever.

Cox claimed that his son-in-law had threatened to take his life, and had listened to evil stories concerning Cook and his (Cox') wife. The case was tried in January last and the death penalty affixed, and on appeal to the Supreme Court the judgement was affirmed."

When Cox was tried for the murder, in January of 1888, it was said that it only took the jury approximately one half of an hour to come to their verdict. Cox tried to appeal it, as the newspaper above mentions, and at one point, his execution was delayed.

According to the Los Angeles Herald, dated March 24, 1888, Cox's hanging was postponed, as it was originally scheduled for March 23, 1888. The final date was set for August 31, 1888, one final meeting at the gallows that Cox would not be able to avoid.

It is apparent that Sheriff Thorn found the entire ordeal unpleasant, as he so did state at the execution and also by the way he had the invitations to the execution designed.

The Sacramento Daily Union even mentioned it on August 24, 1888, that the invitation was printed on a card with a deep mourning border. This is telling. If Thorn so believed that Cox was such a horrid, murderer, he would have had a simple card printed, but this one had meaning, symbolism for that time period. One of not just mourning, but "deep mourning," as the journalist had put it.

|

| The Jail Yard, where Cox was hanged on 8/31/1888 |

"Brave to the Last"

Execution of George W. Cox Yesterday at San Andreas

San Andreas, August 31st, George W. Cox was executed today in the jail yard at 10:30 a.m. by Sheriff Benjamin Thorne [SIC]. The death warrant was read to the condemned man shortly after 10 o'clock, in the presence of several officers and physicians. The Sheriff informed Cox that he had an unpleasant duty to perform and Cox replied, "Go on, Mr. Sheriff, and do your duty."

The condemned man was laboring under some excitement, for his pulse was 140 immediately before being led on to the scaffold, but his manner and words were brave to the last. He walked to and on the scaffold without any hesitation, and assisted the Sheriff in adjusting the straps and the black cap. He made the remark that he was not sorry for anything he had ever done in his life, and as the black cap was slipped over his head he told the Sheriff not to smother him.

At 10:35 o'clock the drop fell and the neck of Cox was broken. He died without a struggle and no pulse was perceptible after the drop. About one hundred persons witnessed the execution." -- Sacramento Daily Record-Union, Sept, 1, 1888.

Spot where the gallows once stood.

Conclusion

George Washington Cox went to his grave with no regrets, or so he stated. But did he really? Were there any actions in his lifetime he may have regretted? It appeared that his emotional letter to his daughter revealed his weakness, his love of his children. Maybe in his mind, if he truly believed his son-in-law was sleeping with his wife, he felt it was a betrayal to his daughter as much as it was to himself. If this rumor had any truth to it at all, it would ruin both marriages, and disrupt the family forever. Maybe Cox just couldn't handle the idea of his daughter's heart being broken, or becoming hardened as his had.

Will we ever know if the stories he believed about his wife and his son-in-law had any merit at all?

Unfortunately, only the people involved in that event that took place back in 1887 know the truth to that story. We can sit and speculate all we want, but we may never know the truth. Cox could have been within his rights to believe his wife was being unfaithful, he may have been threatened by his son-in-law as he stated. Those rumors could have had truth to them. On the flip side, Cox could have been believing lies told to him by others, or perhaps even ideas that he came to on his own.

Was Cox's mind troubled? Did he truly abandon his family for years on end? Or was he working on any job he could to send money to his family, in order to support them? How will we ever know for certain? Unless we have actual records to state either or, we will never know for sure but the story itself was one I couldn't pass up on sharing with all of you.

As many times in my history hunting, Roland and I come across stories that literally fall into our laps. We aren't necessarily looking for them, most times we are searching for something else and those other stories just happen to find us. I am then compelled to tell these stories of the forgotten, no matter whether they are: infamous, famous or unremembered, because I believe every grave has a story to tell, and as long as I am here, I will remain a voice to the voiceless so they will be forgotten no more.

|

| Final Resting Place of G.W.Cox |

(Copyright 2022 - J'aime Rubio www.jaimerubiowriter.com)

Photos:

Grave of George W. Cox, Peoples Cemetery, San Andreas (Copyright, J'aime Rubio)

Photos inside and outside of San Andreas Courthouse/Jail/Jail

yard (Copyright, J'aime Rubio)

Sources:

Motherlode Memories, by Dr. R. Coke Wood & Leonard Covello, published by Valley Publishers, 1979.

San Andreas Museum (photos)

Newspapers: Amador Ledger, 11/12/1887; Amador Dispatch, 11/19/1887; Sacramento Daily Record-Union, 8/24/1888; Amador Dispatch, 9/1/1888; Sacramento Daily Record Union, 11/05/1887, Los Angeles Herald, 3/24/1888; Sacramento Daily Record Union, 9/1/1888; Stockton Record, 5/4/2007.