“History will always repeat itself.” Those were the words of Greek historian Thucydides, spoken in the 5th Century BC, and yet still today, no truer words could be spoken.

In fact, in my line of work researching the past, I have

often found tragedies which seemed to repeat themselves in a later generation,

almost as if it were some sort of vicious cycle. As if a sinister, cosmic wheel kept spinning in the same circle within a family lineage, like a broken record,

repeating the events with no rhyme or reason as to why.

Today, I am going to share with you the story of Albina Keyes,

but we will also take a deep dive into her family history to see just how death

seemed to follow the women in her family, almost as if in a pattern, one after

the other, just in different time periods.

Several years ago, I shared the sad events relating to the murder of Albina. As tragic as her story was, I had no idea that years later, I would come in contact with her great, great grand daughter Adria Bowman, and together we would unravel another family mystery. The odd thing about Albina’s story was that the more we dug into her family history, the more we discovered that this story had all happened once before.

|

| Photo of Amanda Dale |

The year is 1898, and Mary Robinson and her daughter Amanda

Dale are living on the Miwok reservation at Shingle Springs, California. Amanda’s

father, Abraham Dale and her mother, Mary, had split earlier on in Amanda’s

life. Mary remarried two more times, eventually settling down with a Native

American medicine man by the name of William Joseph, and they had several

children together. Mary, Amanda’s

mother, was half Native American and half black, while Amanda’s father was of

English descent.

Amanda was an adult by this time in 1898. In fact, she was 21

years old, with two children of her own. When Amanda was just 14 years old, she

fell in love with an older, married man, and found herself in a precarious

position. The man, Francisco Bergala, a native of Chile, had moved up to the gold country during the Gold Rush and settled there, eventually marrying Susan

Nieda of Sutter Creek. The two had seven children together.

According to documented records, during the summer of 1890, Susan had to undergo an operation for some sort of health issue, and it rendered her an invalid for the rest of her life. Instead of taking care of his wife and children, Francisco left his wife’s care with his children and he took Amanda as his “common law” wife. Soon, his first family found themselves destitute and begging for assistance from the county for financial aid in order to survive.

News spread around the area quickly, and soon Francisco found himself indicted not only for adultery, but also rape, being that Amanda was only 14 years old at the time they had relations. Not only that, but Amanda also soon found herself pregnant, and in October of 1891, Amanda gave birth to her first child, Albina Bergala.

The newspapers relay the

story in the Mountain Democrat dated January 23, 1892, mentioning that the Grand

Jury indicted Francisco, and a guilty verdict was found. It appears as though he

didn’t do any real jail time, as the records stated he faced 125 days in jail or a fine

of $250.

It looks as though eventually Francisco Bergala was out of

the picture, and Amanda started a relationship and eventually married Jack “Acorn

Jack” Nickel, who happened to be her step-father’s nephew. After thorough

research into the case, both Adria and I have come to the conclusion that

Amanda possibly had one other child, this time with Jack.

According to oral histories transcribed of William Joseph,

Amanda’s step-father, he stated that Amanda and her brother Jesseway’s paternal

grandmother, had passed away in Missouri, and since their father Abraham had

predeceased her, an inheritance was owed to the two siblings.

“The grandmother of those two died in Missouri, and

apparently left everything to them, money and a ten-thousand-dollar house in a

town in Missouri. This girl, Mandy said, “Write for me, stepfather, I want five

hundred and fifty dollars,” she said. “The money my grandmother left is said to

be there, left for me.” I wrote her uncle who was called Jacob C. Dale, the

check came.” -- William Joseph, oral history.

Sadly though, Amanda did not keep her personal financial

information a secret and when she became involved with Jack Nickel, she later

found this was a terrible mistake. Once Acorn Jack learned that she had a

substantial inheritance, and after becoming her husband, he took the money and

squandered it on booze and gambling. It lasted a grand total of three months

without Amanda ever having seen one dime of it.

One day while William Joseph was at work, which was just over the hill, a fight between Amanda and Jack ensued. The

newspapers mentioned that it was jealousy that threw Jack into a fit of rage,

and he took his rifle and shot Amanda and her mother, Mary, killing them both.

“Triple Homicide”-- “Last Saturday afternoon, near the

Greenstone mine, at the home of his mother-in-law, Mrs. Wm. Joseph, a quadroon*.

Jack Nickel shot and killed her and his wife, an octoroon.* In shooting the latter he wounded a child

which she was holding in her arms, and having finished his deadly work he

pulled off one his shoes, put the muzzle of his Winchester rifle against his

heart, touched the trigger with his tow and fell dead with the gun by his side.

A little daughter of Mrs. Joseph, twelve years old, was the

only eyewitness. A few minutes after the shooting, George Wade carried the news

to Shingle Springs and notice came thence to the coroner, by whom inquests were

held the following day. For some time, the Indian had been sick and using some

sort of medicine and whether too much of the drug or the devil instigated the

brutal homicide may never be known.”—Mountain Democrat, November 19th,

1898

According to a transcribed account given by William Joseph of what transpired that day, as he recalled it while working with his boss, J.D. Annette:

“Acorn Jack must have been angry that day. There were hunters

shooting there all the time.

I said “I seem to hear shooting.”

“But maybe it’s those hunters,” J.D. Annette said. “I have heard

women crying right over at your house. Let us go and see!”

“We went. We met my daughter running. “He has killed my

mother and my elder sister!” she said.

And J.D. Annette said, “Don’t go! He will kill you!”

“Never mind, I am going, I want to see my wife!”

“Wait, I will give you my gun!”

He gave me his gun, a Winchester. I went to the house. He

(his boss) went to the top of that hill to watch me from there. I saw my wife laying

on her back, dead. Going on, I saw the girl laying on her side. Close to her

lay the little two-month old baby, his bullet had apparently grazed its chin.

I said, “Maybe he is inside.” I ran past the doorway. I saw

that fellow laying in front of me, he

had evidently killed himself, shot himself in the breast. The bullet had

apparently not gone through. I shouted to J.D. Annette, “Come, that fellow has

evidently killed himself!”

We picked up only the two women and took them inside. We did not take that Acord Jack but let him lie in the same place. Then I went to tell the police. A lot of white men arrived. After keeping them for two days, I buried them all. That is what Acorn Jack did there, he killed my wife. That is that.” --- Story # 70, "Nisenan Texts & Dictionary," by Uldall & Shipley, published by University of California Press, dated 1/1/1966.

– University

of California Press, published Jan, 1, 1966., U.C. Berkeley.

No more was ever noted about the two-month-old baby, so there is no information as to where he or she ended up. However, we do know that Amanda’s older child, Albina, who was only 7 years old at the time ended up with her father, Francisco Bergala.

So, one would assume that Albina would go off to live with

her father and things would work out, right? Wrong. Unfortunately, fate had its

sights set on poor Albina, and it was going to follow her to the very end.

History Repeats Itself-

The year was 1907, and by this time Albina was 15 years old. Census records noted that she and her father were living in Plymouth at the time. Like her mother did only a little over 15 years ago, it appears that Albina caught the eye of a much older, John “Jack” Keyes, who was 13 years her senior, and the couple started a sexual relationship. At some point her father must have told her that she wasn’t allowed to see Jack Keyes, because the Amador Dispatch dated October 11, 1907, states that Keyes was arrested for the abduction of Albina. In reality, Albina had run off to be with him, but because Keyes was an adult at the time, he was accountable to the law.

While still in jail, Albina and her father visited Keyes, and

it was decided that all charges would be dropped if he agreed to marry his daughter.

So, the couple were legally wed on January 16, 1908.

Things started off on the wrong foot, so-to-speak, because Albina gave birth to their first son alone, while Jack (and his brother Edward Keyes) were doing time in the penitentiary. They had been arrested for burglary and sent to San Quentin.

|

| John "Jack" Keyes |

Because of “good behavior” the two were paroled early. Jack

was released September 1910, while Edward was released in 1911.

During the time that Jack was incarcerated, Albina and her

son, Johnny moved back with her father. The census records for 1910 shows them

living in Plymouth with Francisco.

When Keyes was released Albina and Johnny went back with him.

Not even a year later, Jack and Albina are in the newspapers

again, this time after their son Johnny went missing. The Amador Ledger mentions

that three-year-old Johnny disappeared, but later his parents admitted that he

had been given away to campers named Mr. & Mrs. Smith, who had recently

lost their own child. According to the Keyes (Jack and Albina) they had given

their child away to the family because they couldn’t afford to take care of

him, as they were in financial difficulties. No one ever found out who these

alleged campers were, and no records have ever been found to validate their

story.

When I read this information, I was taken aback. Something in

my gut said this story just didn’t add up. And it still doesn’t. Steve Jones, genealogist, and Find-a-grave

contributor, whom I have been in contact with for several years regarding

Albina’s story, also thought the story was suspicious, as did Albina’s great-great

granddaughter Adria, as well. All three

of us have speculated that Johnny’s disappearance didn’t happen the way Keyes claimed,

and that perhaps little Johnny met an untimelier ending, and sadly, one that we

will never be able to confirm.

Moving forward, Albina and Jack went on to have more children.

Marguerite was born in 1913, William in 1915, and lastly Marie on March 6, 1918.

According to the newspaper articles discovered by Steve Jones, they state that 5

year-old Marguerite died at a Sacramento hospital on May 10, 1918, which was

the result of swallowing a pine nut which lodged in her throat a few days

before. Her grandmother, Marguerite Keyes Morales, brought her to the hospital

in Sacramento for treatment. The nut had been removed by way of an operation,

but she died from the infection that followed her surgery. She was buried in

the Keyes family plot in Plymouth.

Unfortunately, this would not be the last of the tragedies to

befall Albina or the family itself.

The original article I discovered so many years ago, the very story

that first drew my attention to Albina’s story, reads:

The Tragedy -- August 29, 1918

"Brutal Husband Kills Wife And Child With Axe-

One of the most brutal murders it has been our duty to record occurred

yesterday sometime before noon at the Head place*, about two miles

up the ridge from the Summit House, when Jack Keyes with the blunt side of an

axe crushed the skull of his wife, Bina Keyes, aged 24, and then inflicted a

fatal blow with the same instrument on the forehead of their 6 month old

daughter, Marie Keyes.

The first known of the crime was about 8:30 last night, when Keyes came to the

County Hospital in Jackson and asked Superintendent Murphy for some

poison. Murphy asked what he wanted it for, and Keyes replied that his

had killed his wife and baby with an axe. Murphy told him it was hard to get

poison but Mr. Dodd, the nurse, would take him down town for some, and while

they walked away from the building Murphy quickly called up the Sheriff, who

met Keyes shortly after this side of the hospital. Keyes told the Sheriff he

had killed his wife and baby because a lady told him his wife was an anarchist.

The Sheriff placed Keyes in jail and went to the scene of the murder.

When asked why he killed the child, Keyes said he figured the baby was an

anarchist also. He said he struck his wife several times with the axe before

the fatal blow crushed her skull. After the murder Keyes washed the bodies,

dressed and covered them. He sat around the house during the afternoon, until

the time he came to Jackson.

Keyes showed absolutely no signs of being intoxicated, as testified to by both

Superintendent Murphy and Sheriff Lucot at the inquest held here today by

Coroner Dolores A. Potter.

During the inquest Keyes, angered at the removal of a stove poker from his

reach, sprang from his chair and attacked Deputy Sheriff Ford. Instantly a

dozen men were on the job and a well-directed blow on the murderer's neck by

Telephone Manager Watts, a juryman, floored the belligerent.

When asked if he had anything to say, Keyes said he wanted to be hanged. Other

than that, he made no further statement. Keyes has been in trouble before. It

is said he and his wife quarreled frequently. She feared to return to him from

the County Hospital, where the baby was born on March 6 of this year."

---Amador Dispatch (8/30/1918)

*(The Head Ranch was located east of Sutter Creek/Sutter Hill, up Ridge Road, near the Summit Ridge. This was the ranch owned by James Head, the step-father of the infamous Black Widow of Amador County, the one and only Emma LeDoux. She was made infamous for the brutal murder of her husband Albert McVicar in 1906, as well as being a bigamist. To read about her story, please go to the link here: https://jaimerubiowriter.blogspot.com/2018/05/emma-ledoux-black-widow-of-amador.html )

By October of 1918, Keyes was declared unfit for trial due to being “insane,” and was sent down to the Stockton State Hospital for treatment until fit to be tried for the murders. By May 23rd, 1919, Keyes made headlines once again, when he escaped from the Stockton State Hospital by “slipping out of line passing from one yard to another.”He was on the lam for about 6 months when Amador County Sheriff

George Lucot received a tip that Keyes might be at the Lincoln Ranch. Quickly,

Lucot went to check out his lead, and sure enough, he was able to apprehend his

prisoner.

One note that I would like to make is that in my research of

stories pertaining to crimes in Amador County history, I have found so many

times that Sheriff Lucot is personally involved in apprehending the criminal. Sheriff

George Lucot was the longest standing Sheriff in Amador County history, and to

my knowledge, the State of California, and possibly even the United States as a

whole, as well. George Lucot became Sheriff in 1914 and retired in 1954, making

his career of a Sheriff a grand total of 40 years.

While investigating the local history within Amador County, I have watched stories reveal

themselves to me, by way of the old microfilms at the library. Case by case,

Sheriff Lucot always seemed to be one step ahead, catching the bad guy

and saving the day. He has become a hero in my book, just as Sheriff Phoenix is

to me, (the very first Amador County Sheriff).

From hostage crisis situations, attempting to spearhead the

rescue of the greatest mining accident in U.S. history, down to hunting down a

murderer, even going across state lines in order to do so, George Lucot saw

it all, did it all, and was prepared to do whatever it took to catch his

prisoner. With his keen investigation skills, he remained the larger-than-life

force that Amador County needed for so many years.

Back to the story-

After being apprehended on November 10, 1919, Keyes was declared

sane enough for trial, but pled guilty on November 14, and was

sentenced on Monday, November 17, by Judge Wood. On November 20,

1919, Keyes was received at San Quentin Prison, but only lasted there for a

week, and was then transferred on November 28, 1919 to Folsom, where he

remained for the time being. The 1920 Census records show him as a “quarryman”

and of course, an inmate, at Folsom. His records note that he was then

transferred to the Napa Asylum on November 16, 1921 – and from there things get

sketchy.

According to notes by Dorothy Pinotti, she claimed he died

while at Napa and his remains were brought back to Plymouth and buried in the

Keyes family plot at the cemetery. However, there are no death records

available to validate this. Even Napa County Hospital was unable to confirm

this with me. You see, there is a John

Keys (not Keyes) listed in the 1930 and 1940 Census records at the hospital in

Napa, but the information on this person does not match our Keyes. For one, John

Keys in the 1930 census states his mother and father are from Ohio, while we

know our John KEYES’ parents were from Ireland and Canada. I scoured through

the patient list for the entire hospital and found a few other “Keys” but no

one with the same name, and no one with matching family background. It is as if

John Joseph Keyes just vanished.

And with no death certificate available on record, I cannot definitively

state that he is buried at the Keyes family plot in Plymouth. So, the

whereabouts of his remains and his mortal ending is still somewhat of a mystery, for now.

So what happened to baby Johnny, who disappeared at 3 years of age?

Did John Keyes really give him away to campers, or was it something more

sinister? Did he kill his own child? How did little Marguerite choke on the pine nut? Was that all just an accident,

too? We know for a fact, John lost it mentally, when he took an axe to his wife

and infant daughter Marie, but was he responsible for more deaths than theirs?

What boggles my mind is the fact that by writing about that one

tragedy so many years ago, a story I had unknowingly stumbled upon, in turn has slowly unraveled and uncovered the skeletons of old family secrets hidden between the

pages of the old archives, just waiting and yearning to be told once more. The names

of those people who hadn’t been uttered in over a hundred or more years, were

once spoken of and their stories brought back to life again.

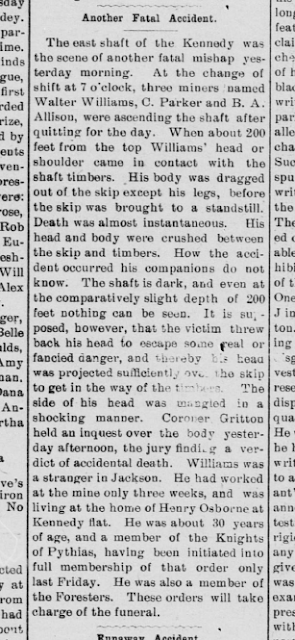

When I initially wrote about the tragic story of Albina Keyes’ death it stuck with me. I was emotionally driven by this story to find her grave, although sadly she has no marker for you to visit. Thanks to Steve Jones’ sleuthing, he found the original sexton cards for the Jackson City Cemetery which provides clues to where Albina and baby Marie were buried, but their graves are still unmarked.

|

| Albina's Burial Card (Sexton Record) |

I believe that Amanda Dale and Mary Robinson are buried on

the native burial grounds in Shingle Springs somewhere, although I am unsure if

the area is accessible, let alone whether there is any sort of marker for them

there at all.

In regard to the other Keyes’ children, we will never know what

happened to Johnny. Marguerite was buried in the family plot in Plymouth in 1918

and William, the one child who seemed to dodge a bullet so-to-speak, was raised

by his paternal grandparents in Plymouth per the 1920, 1930 census records. He

eventually grew up and moved away, and it is his great granddaughter Adria who

contacted me after reading my original blog about Albina.

I hope that one day, by getting enough exposure to Albina’s story, we can drum up enough interest within the community to erect a marker for both Albina and baby Marie at the Jackson Cemetery where they have been resting, undetected and unknown for far too long. They both deserve to be remembered and no longer be part of the forgotten. --

A Big Thank You To: Steve Jones (Find-a-Grave Contributor & Researcher) as well as

Adria Bowman, Great Great Granddaughter of Albina Bergala Keyes.

Copyright 2022 - J'aime Rubio, www.jaimerubiowriter.com

Sources:

Amador Dispatch, 9/30/1918

Amador Ledger, 9/30/1918

n

Amador Dispatch, 9/5/1918

n

Amador Dispatch, 5/29/1919

n

Stockton Independent 9/1/1918

n

Amador Dispatch, 11/20/1919

n

Sacramento Daily Union, 6/3/1919

n

Amador Ledger Dispatch, 11/13/1919

n

Amador Ledger Dispatch 11/21/1919

n

Stockton Evening Record, 11/10/1919

n

Amador Ledger Dispatch, 5/30/1919

n

Amador Ledger Dispatch, 10/25/1918

n

Amador Ledger Dispatch, 5/17/1918

n

San Francisco Call, 11/14/1898

n

Mountain Democrat 11/12/1898

n

Amador Ledger, 8/11/1911

n

Amador Dispatch, 8/29/1918

n

Amador Dispatch, 10/11/1907

n

Amador Ledger, 1/17/1908

n

Mountain Democrat 1/23/1892

n

El Dorado Republican 11/15/1918

n

1910,1920,1930,1940 Census Records

n

Prison Records, Folsom & San Quentin

n

Find-a-grave, Ancestry & Family Search

n

Family tree records, from Adria Bowman

n Story # 70 of "Nisenan Texts & Dictionary," by Uldall & Shipley, published by University of California Press, dated 1/1/1966